From 1980 to 1986 I was the coordinator of this collaboration on the Dutch side. In principle, RIJP employees visited Romania twice a year and a Romanian delegation came to the Netherlands twice a year. See my previous contribution about the Pardina Polder on Flevolands Geheugen.

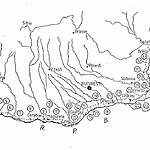

Although the collaboration concerned the polders in the Danube Delta, our Romanian colleagues also appeared to be keen to have information about the best way of water management in the polders along the Danube upstream of the delta. There were no fewer than forty polders along the Danube in Romania and there were quite a few problems with water management. The reason for this was that the soil consisted of clay layers, which swell when they get wet and shrink when they dry out. When they shrink, they become very permeable due to the formation of cracks, but when they swell, they become more or less completely impermeable. It so happens that most precipitation falls in Romania in May and June. In itself this is beneficial, because then you have the necessary water at the beginning of the growing season. But on those swelling clay soils you should not have too much water, because then they become impermeable and unworkable.

In the communist era, however, people did not pay much attention to soil properties and assumed that the land had to be workable with large machines throughout the year. These machines had to be able to do their work unhindered on large flat plots. The soil scientists and water managers had to make sure that this was the case.

We had some experience with this type of soil in the IJsselmeerpolders and knew that you had to dig a trench about ten metres apart and make the plot a little convex in between, so that the excess water could drain well into the trench. This method was out of the question for our Romanian colleagues. They demanded that the soils be drained with subsurface pipe drainage. In the IJsselmeerpolders we mainly have non-swelling clay soils where pipe drainage is very well possible. It was not clear to our colleagues that we could only do this because of the favourable properties of the clay in the IJsselmeerpolders.

During each visit, a Romanian colleague would come into my room with a new formula to calculate the depth and distance between the pipe drainage for the polders along the Danube. I would explain that pipe drainage in the polders along the Danube was not possible and that the land had to be provided with trenches and the plots had to be made a little convex in between. The best way to do this would be to lay the ditches at such a distance that on the one hand they could properly drain the excess water and on the other hand the agricultural machinery could do its work properly in between. My advice turned out to be in vain and was not accepted. Every year, a Romanian colleague would come with a new formula. With the last one, it was too much for me. I ended the conversation immediately and said to him: "Trenches".

Actually, I am curious whether, after the change of regime that has taken place in the meantime, they have now started digging trenches and ploughing between the trenches round as a barrel, as we called it.