In the Bolanha system, rice is grown on ridges in the polders. Although primitive, there is a special water management system that on the one hand ensures drainage and on the other hand offers the possibility to flush out the acids that accumulate in the polders during the dry season with supply of salty seawater. The acids develop when clay soils in marsh areas dry out temporarily or permanently after exploitation. This is a well-known phenomenon in the humid tropics, where flushing out of the resulting acidity can be necessary for years until the acid formation no longer occurs.

Traditional rice cultivation systems functioned well for many years until climate change in 1969 led to a long dry period. The worst affected areas are not only in Guinea-Bissau, but throughout the northern and drier part of the West African coast, including Gambia, Senegal and to some extent Guinea.

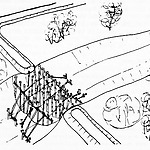

The Geba is a river that starts in Guinea, flows through southern Senegal and discharges into the Atlantic Ocean in Guinea-Bissau. In the Geba, the water level varies due to the tide from 5.60 metres at the mouth to 2.50 metres approximately 100 kilometres upstream. This is one of the rivers where, in particular, since the beginning of the 20th century people of the Balanta tribe have reclaimed approximately 100,000 hectares of mangrove swamps for rice cultivation based on the Bolanha system. According to old tradition, 1.5 to 2.0 metre high dikes were built along the smaller tidal creeks, so that the land behind the dikes would no longer be flooded at high tide. Within the polders created in this way, 0.30 metre high ridges divide the polders into irregularly shaped compartments. Originally, the culverts were made of hollowed-out tree trunks, which were fitted with a plug to prevent the salty seawater from entering. Dams were also built of mangrove trunks in smaller creeks. In the 1950s, this practice was changed and the dams were made of laterite, which was dug from the higher areas.

In the 1970s, a program was realized to build dams in larger creeks. In this way, the number and length of the dikes could be considerably shortened. Concrete sluices were introduced to drain the excess water through the dams. These sluices could also be used before planting the rice to let in salty seawater to wash away the acidity accumulated in the soil.

However, for various reasons, this method has not been very successful. One of the most important reasons for this was the increase in scale. The system requires cooperation among the farmers. In the original small units, the small groups of farmers could usually agree on the water management to be carried out. The construction of dams in the larger creeks created a much larger system around a creek, in which the farmers had to agree on the joint water management for several of the original systems. In several of these systems, this was a step too far. Due to the great importance of good water management for the success of growing rice, the good water management could not be maintained due to the increase in scale and the harvests decreased.

A look at Google Earth shows that many of these traditional systems are still present in the coastal zone of Guinea-Bissau and are apparently still functioning well.